Farewell to Jack Lonergan of Tickincor, Clonmel, County Tipperary, who died on Sunday morning. James Fennell and I enjoyed a lovely day with Jack during the making of the third volume in the ‘Vanishing Ireland’ book series. Here is an abridged version of my account, alongside some of James’s photos.

***

In my young years I went around on a horse and trap but there’s no living for a horse and trap on the road now. When the motorcar came in and the petrol got plentiful, that was the end for the horse and trap’.

As if on cue, a car whizzes by and Jack’s eyes narrow. ‘I never drove’, he says, watching the car vanish over the horizon. ‘I could never have been a driver. The Raleigh bicycle is my machine. I was six or seven when I got my first one. A man’s bike. You’d get more falls off it but you’d get a greater idea of balance then.’

Jack is the ‘general factotum’ at St. Joseph’s Industrial School outside Clonmel. The job title means one who has many diverse responsibilities and derives from the Latin fac totum, meaning ‘to do or make everything’. The name is a legacy of the Rosminians, the Catholic order who have run the reformatory school ever since it was established in 1884.

Better known as Ferryhouse, St. Joseph’s was the brainchild of the Home Rule politician Count Arthur Moore who represented Clonmel in Westminster from 1874 to 1885. Moore loathed the dreaded workhouses to which offending boys were traditionally sent. He conceived of St. Joseph’s as a place where such children might learn some of the skills necessary to improving their general lot in life. Sadly the Count’s legacy was ultimately to be perverted and St. Joseph’s was one of those institutions exposed in the Ryan Report of 2009 for the systematic abuse of the boys within.

Above: James Fennell’s photo of Jack inspired the winning entry of Category B in the 2012 Texaco Children’s Art Competition by the then 14-year-old Shania McDonagh of Mount St. Michael Secondary School, Claremorris, Co. Mayo.

Jack Lonergan (pronounced Londrigan) and his friend Jimmy Walsh started at Ferryhouse in the 1970s. ‘I was in and out of here for a long time and then I became a constant,’ he says. ‘We were helping out on the land, picking spuds and saving hay. There were thirty-five cows at one time and they were milked every day. There was two other men then, Willie Norris and Pat Lyons. Pat was constant on the cows.’

Jack was also assigned to look after the school ponies which graze today in a meadow behind the school playground. ‘That one is a bully for his belly,’ he says, watching a hefty piebald called Magnum throw his head into a hayrick.

Jack has worked with animals all his life. His father was a cattle farmer. ‘We always had seven cows for milk and butter,’ he says. ‘We’d give some of them funny names. There might be a light, thin cow and we’d call her ‘the Heavy One’.’

As children, Jack and his sisters made butter which their father sold to the Creamery. Jack often helped his father drive the cattle into Clonmel for the monthly fair. On those days the Tipperary town was awash with farmers from the outlying parishes herding their cattle down the streets with great roars and considerable humour. ‘We’d sell the cattle up in the Mall’, he recalls. ‘Big cattle were up Johnson Street by the chapel, small cattle were up the Main Street, sheep were above at the West Gate and horses were back in the Mall again.’

‘The fair was always busy but there were no great prices going. It was a day out, I suppose, but we were young and we looked forward to anything. If they made the money, they’d celebrate. Some wouldn’t come home afterwards at all if they could avoid it.’

John Lonergan, Jack’s grandfather, came from Ardfinnan, a village between Clonmel and Cahir on the River Suir. A modest farmer, he kept a few pigs and cattle. During the 1920s, Jack’s father Daniel relocated to the townland of Tickincor on the outskirts of Clonmel. The nearby ruins of Tickincor Castle were all that was left of a once formidable three-storey fortress built during the reign of James I.[ii] It’s last inhabitant Sir John Osborne died in 1743.

Jack’s mother Maggie was a Kelly from Rathgormack, Co. Waterford. She grew up beside the ruins of the Augustinian-built Mothel Abbey. In her grandfather’s day, many from Rathgormack left for the “New World”, settling in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, as well as New York and Boston.

Jack and his sisters were all born at Tickinor. As well as cattle, their father kept a horse and a cob. ‘The one horse is no good. You’d have to have the second one to get anything done.’ Jack often rode up on the cob to get around. The family had no car although if there was a funeral far away, his father would hire one for the occasion.

Jack was educated on the opposite side of the River Suir in Newtown Anner. To get to school during the fishing season, he often went down to Derrinlaur where he met the Walsh brothers, Paddy, Johnny and Jimmy. The four of them would lower a long, narrow fisherman’s cot into the river and paddle across from one bank to the other, keeping their eyes (and occasionally their nets) alert for any passing salmon. Amongst those whom the boys met on their daily voyage were some of the dexterous cot fishermen from the Suir whose skills were prized as far away as Newfoundland.

Jack realised that if he was to earn a living after school, it would be up to his own initiative. The Lonergan farm was too small to bring in any real income. He joined forces with Jimmy Walsh and the two became something of a double act. They started off picking stones for Geoffrey Wilkinson who had been gifted the Gurteen Kilsheelan estate by his uncle Count Edmond de la Poer in 1968.[iii] ‘Mrs. Wilkinson would come for us in the morning, about 10 o’clock, when we had our jobs done at our home place.’

The Wilkinson’s then gave them other work – making silage, erecting fencing around a paddock, harvesting corn. ‘The weather was an awful drawback’, Jack recalls. ‘It could put a lot of work and hardship on you’.

During one fearful wet season, he remembers Mr. Wilkinson eyeballing seventy acres of rain-sodden barley with dismay. ‘If I could just get enough barley to do the cattle, it would be okay,’ he pleaded. When the corn was eventually cut, Jack was impressed when Mr. Wilkinson hired an enormous electric fan to successfully dry the crop out. After Mr. Wilkinson’s premature death in 1982, Jimmy Walsh ‘stayed on constant’ at Gurteen while Jack became ‘constant’ at Ferryhouse.

Jack has a strong empathy for the Ferryhouse boys. ‘There were up to two hundred here at one time. Their parents weren’t able to provide for them so they came here and stayed until they were old enough to get a job. A lot of them went into the army afterwards and some headed off to England.’

Jack never married ‘and thank God for that’, says he. With eighty years under his belt, he is perhaps at maximum ease when ambling around the paddock of a mild spring morning with Magnum and the other horses.

‘There was a barber in Clonmel who used to say, “When you’ve gone over forty, your years are getting scarce.” We have no value on our youth. It goes too quick. But youth is great. You can hope when you have no hope.’

With thanks to Nicola Everard.

****

Jack died peacefully at the Fennor Hill Care Facility in Urlingford on Sunday 26 July 2020. He was laid to rest Killaloan Cemetery after a funeral mass at St Mary’s Church, Gambonsfield, Kilsheelan.

****

www.turtlehistory.com

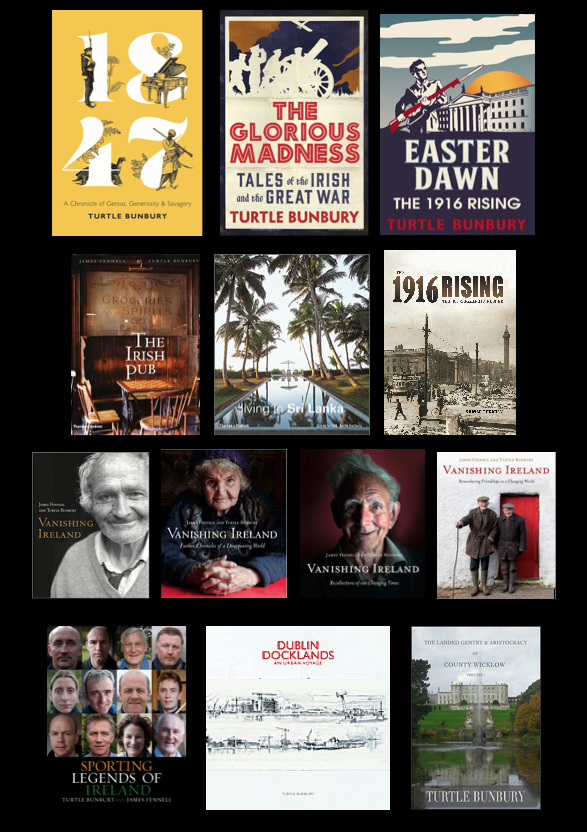

Turtle Bunbury’s books are available from Dubray’s, Eason’s, Amazon, Kennys.ie, Book Depository and most reputable bookshops across Ireland.

July 29, 2020 at 9:22 pm

It is only a short history of Jack lonergan and very interesting, I can imagine if the story of Jack’s

life was put to paper it would be a lovely read I must read that book you have mentioned best regards

LikeLike

November 2, 2021 at 2:21 pm

Thanks Paddy, for the record I am relocating Jack’s story to my new website at https://turtlebunbury.com/document/jack-longeran-1930-2020-general-factotum-of-st-josephs/

LikeLike

July 30, 2020 at 10:27 am

Such interesting reading

LikeLiked by 1 person

October 28, 2021 at 2:00 pm

Fascinating account. One minor quibble: Ferryhouse wasn’t a Reformatory, it was an Industrial School; it’s population was mostly children from families who were too poor, or lone parent families. And most of the children were transferred there from Junior Industrial Schools where the children were placed when babies.

LikeLike

November 2, 2021 at 2:19 pm

Thank you, I have actually just relocated that story, with your useful update, to my new website at https://turtlebunbury.com/document/jack-longeran-1930-2020-general-factotum-of-st-josephs/ … much appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person