Another wonderful man gone onwards to ‘the great beyant’. Charming, ingenious Sam Codd of Aughrim, County Wicklow, passed away on 22 January 2019 in his 94th year. We met Sam at his home about this time eight years ago for a merry afternoon, after which I wrote the following account of his life and times for the third volume of the ‘Vanishing Ireland’ series. The photos are by my colleague and old pal, James Fennell.

*******

Should you ask Sam Codd what a bone-setter does, he is quite likely to suggest that you throw your leg up on a stool so he can break it and then show you how to set it again. ‘If a leg is broke,’ he explains, ‘I put a splint on it, tie a bandage around and put you in plaster of Paris. The bone will fix then.’

He learned the skill from his father. ‘He used to set bones and I’d be tinkering around with him.’ At length he began bone-setting himself and ‘then one lad would tell another’ so that before long, ‘they started to come here from all over the country.’[i]

‘In cattle you have to leave the bone in plaster for about six weeks. In sheep it’s a little less, about a month. But it’s hard to set a horses’ leg unless they are under five years old. A horse has no marrow in his bone. The day a horse is foaled, its leg is as long as it ever will be. It never grows anymore but it thickens up. If you look at a horse the day it’s foaled, there’s a certain place to measure, from the point of the shoulder to the fetlock. Turn that up and that’s the height he will be when he’s done growing. It’s curious of them isn’t it?’

Horses have been a massive part of Sam’s life since he acquired a stallion pony at the age of twelve.[ii] His home, Granite Lodge Stud, is well known in equestrian circles as “The Home of Sammy’s Pride”. Sam purchased this sturdy stallion as a foal and stood him at the stud for many years. ‘He has foals and fillies all over the place! One went to England and won Horse of the Year three years running.’ [iii]

Sam was also famed for the manner in which he trained his horses upon the hilly meadows rolling around his home. He was often to be seen exercising them in his blue trap, pulling at his braces, tipping his cap at passers by. He also farmed the land with his horses. ‘Now it’s all tractors and pressing buttons but in that time everything was done with horses, working and walking alongside them all day, ploughing, harrowing, raking hay and everything.’ Sam continued to work his horses after he ‘got a tractor, same as everyone else’. But eventually he conceded defeat and gifted his last two mares to his daughters.[iv]

He has a handful of well-thumbed photograph albums in which his beloved equines graze, jump and occasionally dance. ‘Anything I asked that lad to do, he’d do,’ he says of one trusty steed. ‘If I told him to lie down, he lay down. If I told him to roll, he’d roll. I told him to stand on his hind legs and he done that too.’ He taught another horse how to sit down in a chair.

Sam was born in October 1926 and reared in Ballysallagh, near Hacketstown, County Carlow, on a farm which his brother now runs. ‘My people were there six or seven generations’, he says.[v] His father William Charles Codd married Susan Hawkins, a farmer’s daughter from Killybeg on the western slopes of Keadeen Mountain.[vi] Susan’s grandfather was a rugged Protestant mountain farmer called Sam Hawkins who married twice. He had twelve children by his first marriage and thirteen by the second. ‘It wasn’t just Catholics who had big families,’ concludes Sam. ‘At one time I had forty eight first cousins and forty of them were living around the Glen.’

Sam was the youngest of William and Susan’s children. ‘You could say I was reared on goat’s milk’, says he, referring to a puckaun (goat) he owned from an early age. ‘I always had goats.’

He left his school in Hacketstown shortly before his fourteenth birthday to help an elderly neighbour with the harvest and threshing. ‘And I was never short of a days work after that,’ says he.

He always made sure he earned his keep. ‘If you didn’t mind your job, you’d get a kick in the arse on a Saturday night and someone else would be in on Monday morning. You can’t sack anyone like that now – you have to give them redundancy!’[vii]

Days were long and there wasn’t much to do in the evenings. ‘You might sit by the fire and that’d be it. Next thing you’d get up in the morning and go back to work. We didn’t go to the pub at all really. There might be an odd card game or something in a farmer’s house. And there used to be dances after the threshing. They were great auld crack. I remember one lad, a fecker for doing tricks, who wasn’t asked to the dance. So he got a ladder up to the house and threw a grain sack over the chimney and smoked out the people inside. He said, “they asked me to the threshing, but they didn’t ask me to the dance”.’

In 1945, a bachelor cousin of his father passed away and Sam, aged only twenty, ‘fell into this place’, the forty acre farmstead on the road to Aughrim where he now lives.[viii] The house was thatched at the time but when combine harvesters took over from manual threshers, ‘all the straw was broken up so we done away with the good thatching’ and went for asbestos instead. In the summer of 2010, 85-year-old Sam replaced the asbestos with proper slate.

‘You had to be very fit to farm,’ says he. ‘That’s why I’m so fit still. I was never sick in my life. We used to be up at six o’clock every morning and to bed at ten or eleven at night. That was the custom. We had to work for a living. But we were all happy and healthy that time. It was a great old life. People had very little money but they were happy.’[ix]’ One particularly stocky job involved carrying grain barrels. ‘We’d be lifting the barrels and there’d be maybe twenty-three stone in a barrel. It’d take two people to lift it but there was a certain way of doing it.’

For a long time, Sam farmed cattle, thirty, maybe thirty five at a time. He milked them all twice daily, pumping the milk into tall aluminium cans which he then wheeled out to the roadside in a barrow. ‘The lorry came then and took the milk off to Inch Creamery.’ As technology evolved, so the creamery was able to pump Sam’s milk directly into a bulk tank and that was the end of the can.

‘We were paid on the milk according to the quality, the butter fat and all that,’ he recalls. ‘I was very lucky as I had the highest butterfat going into the creamery. That was because of the sort of cows I had. I started with Shorthorns – they gave good creamy milk – and I had an odd Jersey among them. Then I started on the Friesians and I built up a great herd from around here.’[x]

When the cattle were not in the fields, he kept them in a cow house beside his home. ‘Nowadays, cattle are all in on concrete floors and you might have three of four of them to a cubicle’, he says disapprovingly. ‘That’s why they’re slipping around and getting hurt.’

‘You can train a horse but there’s no great way of putting manners on pigs’, says Sam of his time as a pig farmer. ‘You just have to put up with them and give them the odd skelp with a stick.’ At his peak, he had ten farrowing sows and a couple of breeding boars that ‘went all over the country.’ Sam ran a tight ship and if a sow did not perform according to plan, she was liable to be ‘hanging up by the leg in Duffy’s bacon factory’ before the next full moon.[xi]

‘You’d always have a fat pig that time,’ he says. ‘You killed it and took two stone of salt to cure the bacon. You’d rub them on the table every night for a few nights, and when you’d be done rubbing and getting it cured, you’d hang them up on the ceiling. You had nothing to do then only cut off a rasher and throw it into the pan. And you’d have gravy enough to fry an egg. That time, you wouldn’t kill a pig until it was about twenty stone weight. Now they wouldn’t eat it because they’d think it’s too fat. They’d cut the fat off it! We lived off the fat!’[xii]

In 1947, Sam married Jenny Coe, a kinswoman of the bachelors who owned his farm. She passed away in 1987, leaving him with a son, three daughters and, at last count, fourteen grandchildren and half a dozen great-grandchildren.[xiii] ‘The auld years do slip by,’ says he.

As well as his bone-setting and horse-training prowess, Sam is well-known in the locality as the Morris Minor man. ‘The first car I had was a Morris Minor and I never had anything else,’ he says. ‘I used to travel around a lot, as a bone-setter, and I do be in a lot of the old farmer places and all that crack. I had two Morris’s here one time, one for taking the girls out on Sunday and one for everyday.’

With thanks to Philip Judge, Tara Quirke, Vanessa Codd, Susan Soden and Pamela Soden.

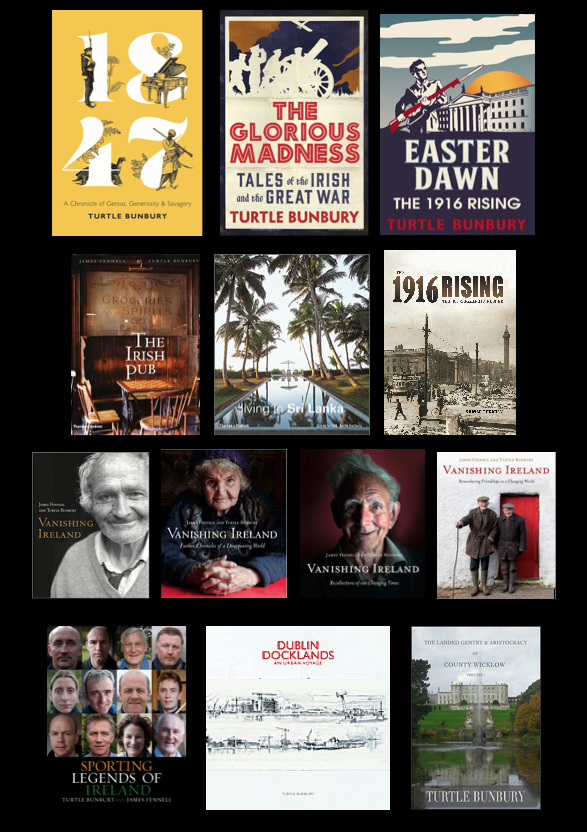

The Vanishing Ireland series and other books are available via all good bookshops nationwide, Kennys.ie and Amazon.

FOOTNOTES

[i] It wasn’t just livestock with broken legs that Sam mended. He also attended to wounded humans, ‘with slipped discs and knocked out fingers and all that. ‘

[ii] ‘When I was a young lad, I always had horses. ‘ had my first stallion when I was about twelve year old. A stallion pony. I had several stallions along the way. And I kept mares here and bred with them and all that crack.’

[iii] ‘I used to keep horses and stallions here and everything. I’ve nothing now. I’m down and out and on the road’, he laughs. Sammy’s Pride, an Irish Draught stallion, was 16 3. ‘He’s over twenty years of age now but still to the good. He’s in Roscommon. I bought him as a foal. Lads used to come here from all over the country with their registered mares and they’d leave them here for a few days to get them in foal. He had a lot of foals and fillies.’ One of these was bred by Bridget Nolan, near Tullow, in a place called Rath, and won the Horse of the Year Show in England three years in succession.

[iv] ‘The last two mares I had here I gave to my daughters – one to a daughter living outside Bunclody and the last mare I had, Aughrim Mist, I gave to another daughter who is married up in Carrigallen, County Leitrim. She bred several foals from Sammy.’ Purple Joey was another beauty he bred but he was hit by the colic and eventually put down.

[v] They are distant cousins of George Codd in Paulville, as well as the Codds who live near Rathdrum, County Wicklow.

[vi] Susan Hawkins was born in 1890. Her father, Sam Hawkins, was born in 1850 and married twice. He had 12 children with one wife and 13 with another wife Mary Anne. See 1911 census: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1911/Wicklow/Donaghmore/Killybeg/888967/ They are distant relations of the late George Hawkins (qv).

[vii] ‘When I was thirteen I spent the summer holidays working for an auld local farmer and when school started again I didn’t go back. The hay had to come in and then the harvest came in. and then we used to go around for a bit of threshing for the neighbours. I left a month before I was 14 and I was never short of a days work after that. That was it. You minded your job then because if you didn’t, you’d get a kick in the arse on a Saturday night and someone else would be in Monday morning. You can’t sack them now – you have to give them redundancy! It’s hard to get lads to work with farmers now.

[viii] ‘I fell into this place from cousins of my father here. I came here in 1945. There was three auld men here. They were all in their 70s. Two never married and worked around the country and retired back here. The other was an invalid in a wheelchair. They were Coles [or Coe’s?]. Their father married a woman who didn’t like the name Codd and changed it to Coe. They eventually died over the years and I came into this place then.’

[ix] ‘Most people have money now – some of them have too much.’

[x] ‘I was in the cows here for a while. I had thirty, thirty five cows and I’d wheel the milk in milk cans out to the road in a wheelbarrow before the lorry came and took them to Inch Creamery. Then there were bull [bulk?] tanks and the lorry collected it the same as the lads with the petrol, and he took the whole tank and that was the end of the milk can. We were paid on the milk according to the quality, the butter fat and all that. They were very particular about it. I was very luck as I had the highest butterfat going into the creamery. That was all because of the sort of cows I had. A lot of the lads went into different breeds of cow. I used to go to the auctions and buy a lot of springing heifers from Rothwells of Tinahely and so on. She’d calve in the spring then.’

[xi] ‘You’d sit up with sow the night they’d be farrowing. I bought one sow who was expecting and she had only the one pig. But I was lucky as three other sows farrowed that night and I took a few pigs off each of them and so she raised ten pigs. The next time she had only three piglets and I said that’s enough and next time she’s was hanging up by the leg in Duffy’s factory. She was never going to have any number’.

[xii] ‘When we had the milk cans we’d get back the skimmed milk to give to the pigs but when the bull tanks came in, that done away with that. They changed the system so I had to get meal lorry come around every Saturday from the co-op at Rath near Tullow. But at the end of it you’d have nothing only a heap of dung and it was costing you. So I got rid of the pigs then because the meal was so dear, feeding them.

[xiii] I married a lady [in Kilpipe church] who was reared in a cottage over the road. Her father was a brother of the Coe lads who lived here. Jenny Coe was her name. We had four chaps, three girls and Vanessa’s husband. The girls are now scattered all over the country. One in Leixlip, one outside Bunclody, one in Carrigallen and married to a lad by name of Mervyn Richardson. I have fourteen grandchildren and half a dozen great-grandchildren. About that anyhow?’ I make my breakfast every day but I get my dinner from my daughter-in-law. She lives about a mile down the road and gives me a bit to eat and all that crack. My son drives a lorry for people down Avoca way.’

Leave a comment